We have just had the most splendid family wedding, full of love and special moments, when our eldest son Tom, married Rachel who he met thanks to an accidental Tinder swipe. Family and friends gathered from afar, the rain clouds parted and as they read their vows and tied the knot, the waves crashed on Cresswell Beach. We partied into the night, first to pipes and fiddle in a ceilidh, and then on the beach around a bonfire, dancing under the moonlight. Yesterday we waved them off on their honeymoon to Bali, the same day, 8th August, as Tim and I celebrated our own wedding anniversary. We’ve been married for thirty-six years now, and I wanted to write this morning about how a chance encounter on a beach whilst on our honeymoon, led to being invited to a Berber wedding, then later discovering a funeral.

We now go back to 1987 and after a busy wedding which like Tom & Rachel’s had a ceilidh in the evening, but there the similarities end. Back then the only choices were to marry in a church, registry office or on-board ship if a willing sea captain was to be found or elope to Gretna Green. We plumped for the church and a traditional wedding. After a night in a country hotel (our honeymoon suite having been done over with silly string & apple pie bed by the best man and bridesmaid who told reception that if anyone else appeared it would be guests mucking around and not to let us in), Tim and I caught a bus down to London and flew from Heathrow to Marrakesh.

We were in Morocco for three weeks and had three different missions. Firstly, we headed to the High Atlas Mountains and climbed Mount Toubkal. There’s another whole chapter to write here, with many adventures along that route, including a nighttime dash over a mountain pass to escape some dodgy geezers! The final week we went by bus along the Valley of a Thousand Kasbahs to the edge of the Sahara Desert. However, that tale will also have to wait. I really would like to put all our Moroccan adventures in a book one day, including returning with the kids and having our luggage disappear, trekking once more into the desert, sleeping under the stars and witnessing a meteor shower. It is the middle section, when we went to Essaouira that I want to write about today.

Being the independent travellers that we are, we went everywhere by bus or grande taxi. After much haggling about how much we would be prepared to pay to put our bags on the roof (little did we know we’d be charged to take them off again), we set off from the Bab er Rob bus terminal in clouds of red dust. It was August, and Marrakesh in August is hot. It is like opening the oven door on a Sunday roast every time you stepped out of the cool of an air-conditioned hotel room. Sweat poured in rivulets down our bodies and we headed to the first stall we found for a bottle of cool water, always checking that the seal on the top was still intact and hadn’t just been filled with Moroccan tap water. The bus was stifling, crowded, and smelly and I lifted the glass on the window to open a flap to let in a breeze only to find the dust from the road blowing in and I was being shouted at by my Moroccan passengers, hands flapping and much tutting, ‘La, la, la!’ No, no, no! It hadn’t occurred to me that opening the window would make the bus even hotter. An older woman, with brown hands adorned with intricate henna designs, leant across, fastened the window and yanked the curtain across. The view was gone, but the shade was welcome. I’d know better another time.

Three hours later we arrived in Essaouira on the west coast of Morocco, where a welcome breeze from the sea, and the smell of grilled sardines from the food stalls on the harbour greeted us as we walked the streets to the Hotel des Remparts, a budget hotel, built in the ancient sea walls. We passed workshops where the sounds and smells of cedar wood being turned on pole lathes and chipped at by chisels greeted us and filled our nostrils. We still have an inlaid bowl and wooden camel bought there. That afternoon, we sat on the beach, right by the ruined castle made famous in the Jimi Hendrix song, Castles in the Sand – it really did seem to float out in the sea. I read that Jimi, along with his mates had tried to buy Diabat, a small village along the coast back in the heady days of the sixties. As we sat watching the waves, a young Moroccan lad of slight build, with a shock of curly black hair, wearing a clean white polo shirt, smart trousers, and flip flops approached us,

‘May I sit with you and practise my English?’

We were instantly wary. What did this guy want to sell us? Was he about to rip us off for something? However, we invited him to sit down and as we chatted, it seemed he really did just want to practice his English. Abdul wanted to get to England one day. We talked about this and that, were not the font of knowledge he had hoped for about Manchester United but could tell him plenty about how we lived, our lives and our universities which he was particularly interested in.

‘My aunt will cook you a couscous meal. You come to my house?’

We’d been warned of situations like this, of being befriended by locals, taken back for couscous meals then charged at knifepoint for the privilege. We weren’t sure. We said we’d think about it.

‘Meet me at Café France at 4 pm.’ Abdul said, then walked away.

I had a hunch he was genuine. There was something about him, his body language, his gentle disposition, and after some discussion, we said we’d go for it. Best decision ever!

It wasn’t long before we were weaving through medieval streets in the old medina where Abdul shopped for vegetables and carried them in stripey plastic bags to the home of his aunt and uncle. As we crossed the threshold through an ancient wooden door in a wall and entered a courtyard it was like stepping back in time. Buildings three stories high surrounded it, the floor bare ground, everything old, so old, with small doors to rooms, that led from the central square. Abdul stepped into the dark of one recess, and once our eyes adjusted to the gloom, I saw an old woman, scarf over her head, dressed all in black in traditional Moroccan kaftan and long baggy trousers, who was squatting in front of a bucket and bowl. I watched as she flicked water into a bowl of dry couscous and then rubbed it with henna’d palms.

‘My aunt makes couscous the tradition way.’ Abdul explained.

‘How do I say, ‘that’s good?’ I asked.

‘Muzyen’ he replied.

‘Muzyen’ I said, and to woman, and touched her arm. She looked up at me with watery eyes, her face lined, a scarf around her head. She motioned for me to squat next to her and she took my hands in hers and showed me how to add water to the couscous to prepare it for steaming.

‘Eefoolki’ she said, looking from me to Abdul.

‘She says you’re pretty.’ Abdul said.

In another recess, three men sat on cushions on the floor around a small table. Adbul invited us to sit with them. His aunt appeared with a tray with six small glasses and a traditional silver Moroccan teapot. Mint tea. The staple drink of Morocco. His aunt went back to the meal preparation. I called ‘Shokran’ after her, but she was gone, back to her kitchen. Abdul’s uncle was introduced, and his brother and cousin. The uncle poured a glass of steaming mint tea and then poured it back into the pot. The smell of mint was delicious. He poured again, reaching high into the air with the teapot. ‘The higher the pour, the more honoured the guest,’ Abdul explained, ‘more bubbles’. I wished I knew more Arabic but was grateful for my newly learnt word: ‘muzyen’, I said and smiled. Three toothy grins beamed back at me and nodded their approval.

I had A’ Level French, and this was useful in the city of Marrakesh, but these guys spoke Berber. They had no French. We are big believers in trying to learn some words of any language, ‘la shokran’ (no thanks) being useful when being hustled in the Djemma el Fna back in Marrakesh, but here, words for good, pretty and thank you seemed far more appropriate.

As tea ended, the aunt appeared again with a tagine, that pottery conical cooking pot and lifted the lid. ‘Couscous aux sept legumes’ Adbul explained, and everyone dived in, eating with their right hands. They laughed at our efforts to eat couscous with one hand and the mess we made but it was all in good humour and once we were shown how to rub it into a ball with thumb against palm, it was much easier.

‘Why does your aunt not eat with us?’ I asked.

‘Men and honoured quests only.’ Abdul said. She would eat what was left. Hardly fair, but that is their custom and religion. Although a woman, I was treated as one of the men, an honoured guest.

Needing the loo, I was shown to a small cubby hole, where a hole was in the ground and was offered a small pail of water. Did I need this? It was not for washing hands. I was careful to mouth breathe until well clear of the netty.

‘You come to Berber wedding, tomorrow.’ Abdul said. He was stating a fact, not a question.

‘Erm, yes, ok?’ Tim said, looking at me with raised eyebrows.

‘Yeah, sure,’ I said. Again, right decision made.

*

We took one rucksack between us, leaving the rest with Abdul’s family. It would be safe there, we were sure and set off in a grande taxi, the system being that the driver waits until his taxi is full before setting off, often with two people in each seat. Personal space was not sacred and with the heat, it made for an interesting and intimate ride. We paused on the road for a passing funeral procession and Abdul explained that because of the heat, the dead had to be buried straight away. It was with some relief that we got out in front of a large prickly pear and Abdul set off along a dusty track, insisting on carrying our bag. We walked for about two hours, and despite wearing a wide-brimmed hat and sipping on water as we went, I began to falter, feeling faint and very tired.

After some discussion with a passing man on a donkey, I was hoisted up into his saddle and given a ride the rest of the way. I’m not sure if the guy was intending to go the way we went, but he did. I was very grateful and felt too rough to argue.

We rounded a corner and saw a crowd on a mound of red earth in front of buildings made from the same red earth and straw. A woman sat on top of a donkey, totally shrouded in cloth. Only her eyes were showing. Abdul explained this was the bride, and she was going to go to her mother-in-law’s house to live in solitary confinement for a few days. During this time, she would weave a rug, and in the symbols used, she would share with her own family whether she was happy with her new family. As Abdul was speaking, the children and villagers spotted Tim and I. They rushed over, touching Tim, who at 6 ft 2” towered above them. Adbul explained they never got white tourists out here. We were led by the hands to a compound, where, under the shade of handmade blinds, we were served mint tea with the men.

We were questioned about all sorts – did we grow tobacco? Is King Hussein not king of all the world? How did we manage to get passports? Adbul translated all the time.

Abdul explained that we would stay here tonight, with these people before going off to the wedding tomorrow. Tim was to sleep on rush mats under the stars with the men, and I would go and sleep with the women and girls.

Malika, who baked the family’s bread in a clay oven, would look after me. She showed me how she baked bread in the family oven, then talked about her daughter who needed a cataract operation to restore her sight, but the family did not have enough money. I thought of the new prescription glasses Tim and I had bought just a few months before and how much they had cost. It did not seem fair. This little one would lose her sight completely without the operation.

In the women’s quarter, my hands were painted with a Henna design and a traditional red Berber Scarf was found and wound around my head. As night fell, and we settled down to sleep together, I reached into my bag for my contraceptive pill. The other women found this most interesting. I swallowed a tablet, and then said ‘la bebe’, miming ‘no’ with a sweep of my hand, then rounding an imaginary pregnant belly. Ah! ‘muzyen, muzyen’ they said, clapping, then hands outstretched for a pill. How to explain that just swallowing one tablet did not mean they could then go off with their husbands and make love behind the prickly pears with no consequences? I got the message across using mime, French and the odd Berber or Arabic word, and as the laughter rang out, I was handed a small sprig of mint. The other women had shoved the mint up their nostrils. Someone had farted!

I slept surprisingly well but was woken early by a crowing cockerel and then was taken outside to compound to pee with the other girls. Mint tea was served, and fresh bread was handed around with a pot of honey for dipping, and almonds and dried apricots. The day was already hot, the sky cobalt blue in contrast with the whitewashed walls of the buildings. The family started to prepare for the wedding.

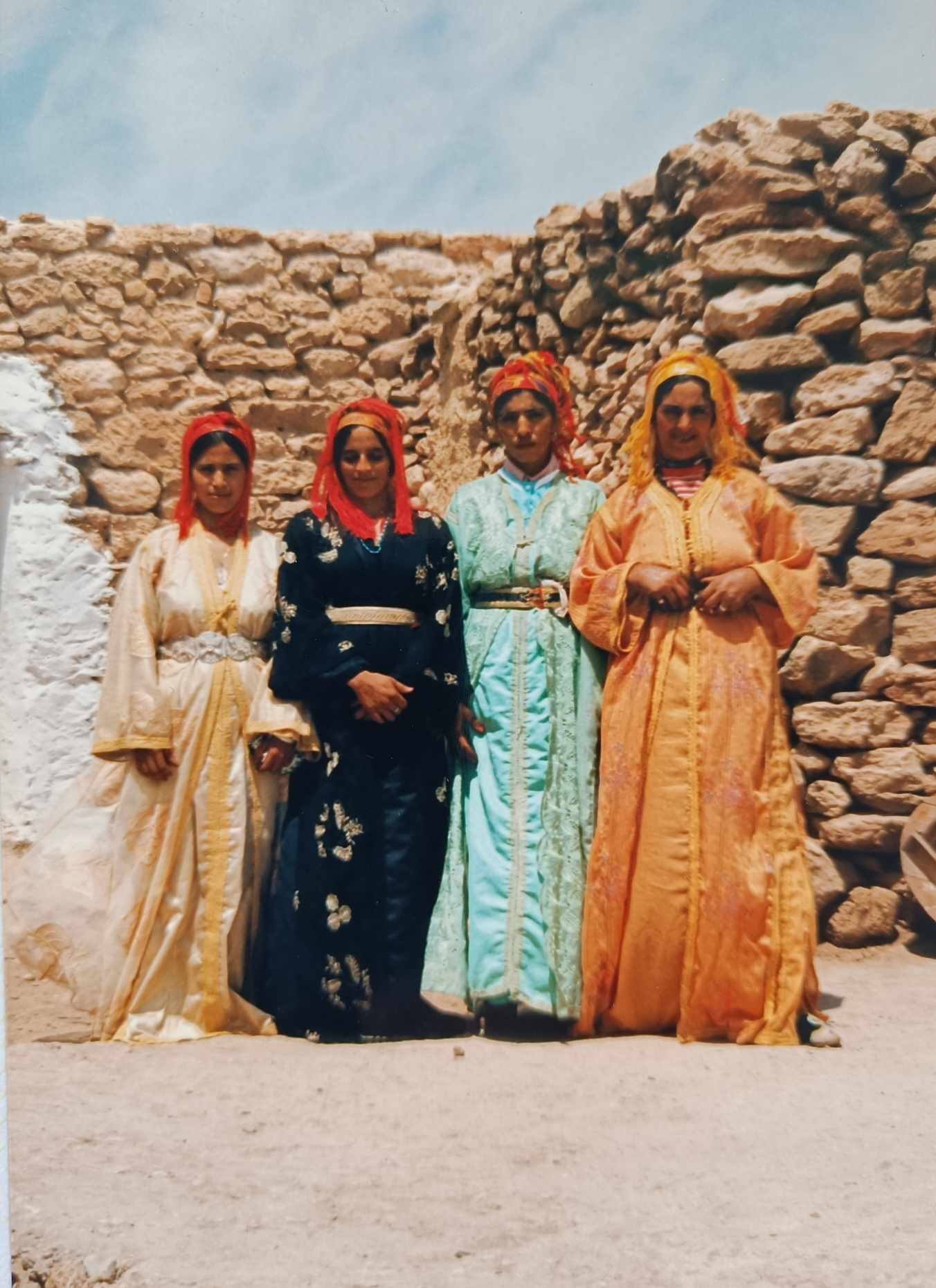

Four beautiful young women came from a room and lined up before me. All wore red Berber headscarves and beautiful satin dresses that grazed the ground. One yellow, another turquoise, one orange and one black with beautiful embroidery. They beckoned for Abdul to translate.

‘They want to know who is the most beautiful,’ Abdul said.

How could I choose? This was an impossible task. They were all exquisite, their dark hair and brown skin so beautiful against the dazzling bright colours of their robes. I did not want to pick one over the rest.

‘They are all beautiful.’ I replied.

‘They want to know who is wearing the best dress’ Abdul said.

I looked along the line. The youngest girl on the end, who had taken me out to show me where to pee in the morning was looking hopeful. I pointed, ‘she is’ I said with a smile.

The girl ducked inside the building and came out again wearing her work clothes. She handed me the dress.

‘Oh, I cannot! La, la.’ I said.

‘You must,’ Abdul said, ‘she wants you to wear her dress to the wedding.’

As I write this now, 35 years later, the emotion still wells up inside me. The warmth and generosity of these wonderful people knew no bounds. We had more clothes and possessions in our one rucksack, let alone what was left in Essaouira and in our homes back in England than these folk had between them all. They had one set of everyday clothes for working in and another for best. The few pots and pans were shared between families, and apart from bowls and tea glasses, I could see no other possessions to speak of. What a difference to our lives and I thought of all the wedding gifts we’d received, the bone china dinner service, canteen of cutlery, crystal glasses and trifle bowl etc. etc. I wondered whose lives were richer.

I hugged her and took the dress, putting it on. The women crowded around me, banging little drums and making that noise where they waggle their tongues in their heads, forgive me, I don’t know what it is called, but it is a sound that stirs the emotions, and like the call the prayer that rings out across Morocco, brings a lump to my throat and causes tears to tumble. The men mounted donkeys and set off for the wedding and we women began to walk with the children, singing, banging drums and dancing. We would pause to pluck ripe prickly pears from cacti, and wait while other groups of women joined us, walking across dry fields from all directions until we were a throng of womanhood, wailing, singing, dancing and making music together until we reached the farm where the wedding was to be held, and I joined in with the dancing, Malika and I taking centre stage at one point. What an absolute privilege to be here, to be part of this.

We partied long into the evening, no alcohol was needed, just joy, love and a sense of community and family. Tim joined us after a few hours, having been ushered from the room of men because a hashish pipe had come out. They did not think this appropriate for him to see. If only they knew!

We spent the next day and night with another of Abdul’s uncles, helping the family to shell walnuts and almonds, sharing food and sleeping in luxury on mattresses around a cool room. They waved us goodbye, and I turned to take one last photo of these beautiful people.

When we got back to Essaouira, we collected our bag, from Abdul’s family’s house, but we found the aunt weeping.

‘Her husband, my uncle has died’ Abdul said, ‘it was his funeral we passed on the road.’

Turns out he was dying as this dear woman was preparing our couscous meal.

Thank you for reading my piece. I do not charge for my words here, but welcome any sharing of my posts. Subscribe to get them sent straight to your inbox.

You can pre-order a signed copy of The Rewilding of Molly McFlynn, my debut novel which publishes on 28th October. Click on this link to find out more.

What a marvelous experience for you both. How generous those people were to you. It was a lovely 'read' and the photographs are beautiful.

How adventurous you were. And what a great experience. I think we forget what is really important in our lives and get caught up in possessions. Thanks for sharing your memories