Welcome to The Book Room! Come on in and grab a chair as we talk about books and our journeys to get them written, published, and seen in the world.

The connection and support shown to me as a fledging author from the writing community have been phenomenal, so I thought I’d return some love to authors with newly published books and invite them to write a guest blog.

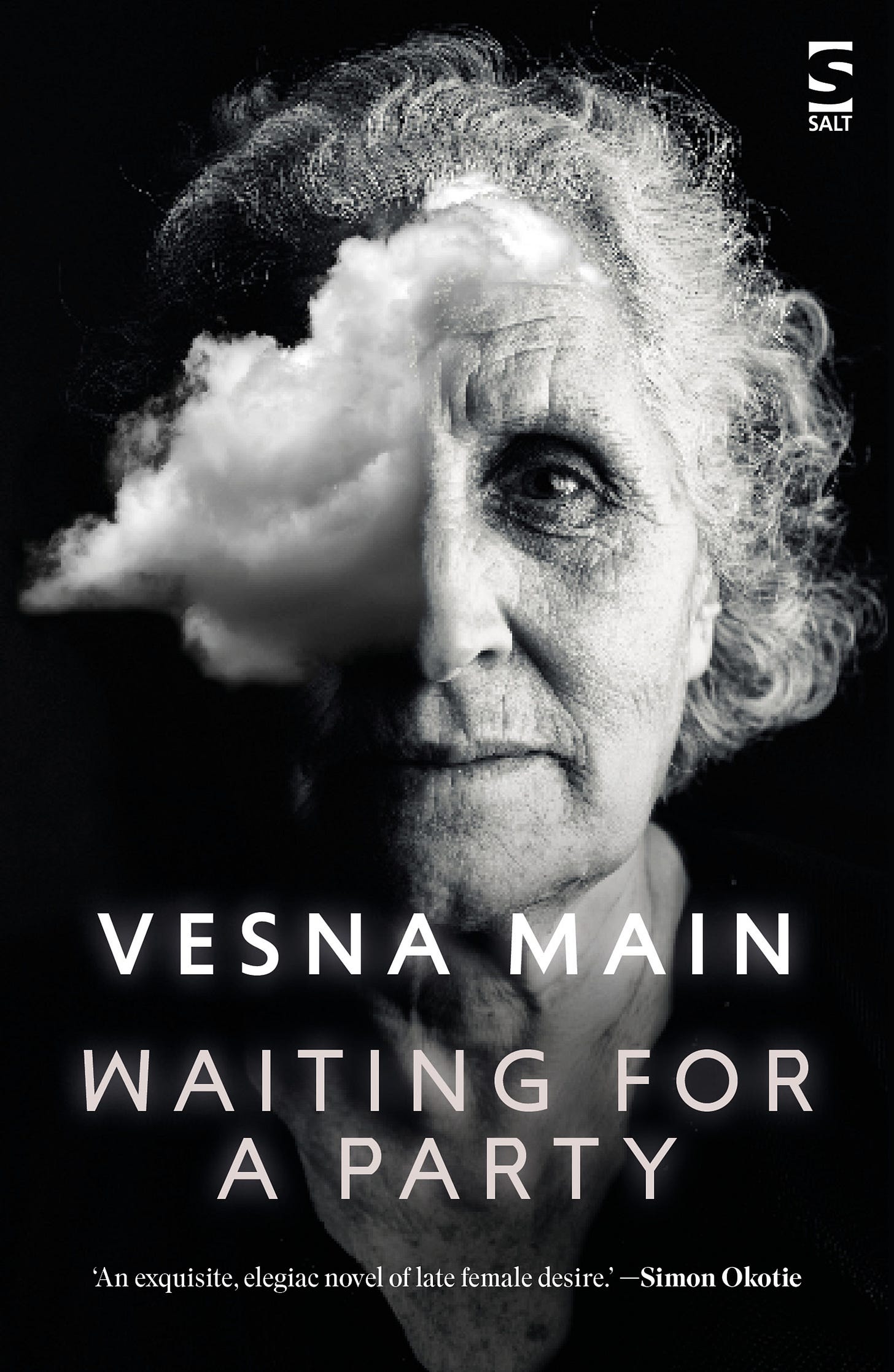

I’m delighted this week to introduce you to Vesna Main and her novel Waiting for a Party, published by Salt Publishing which asks the question,

‘How does an older woman change once she discovers her sexuality?’

My journey to becoming an author

For a long time, I wanted to write fiction but had no language in which to write.

After graduating with a degree in Comparative Literature from the University of Zagreb, Croatia, where I was born, I came to England and studied Elizabethan Drama at the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. But completing a PhD on Christopher Marlowe didn’t mean I could write fiction.

Living in England and no longer reading Croatian literature, I lost the ability to write in my first language. For many years, I worked as a lecturer in literature and also taught on a pilot, creative writing course before I took the plunge and decided to write my first short story. It was a monologue by Victorine Meurent, Manet’s favourite model, who, because she posed naked, was described by patriarchal art historians as a prostitute who had died young of alcoholism but who became a painter and lived into her eighties. Later, my first published novel, A Woman with No Clothes On (Delancey Press 2008), gave a voice to her and to Manet as they worked on his two most famous paintings.

Other works by Vesna Main

Other stories followed as I continued to learn to write in my second language. I am pleased to say that, even after publishing several novels, a collection of short stories (Temptation: A User’s Guide, Salt 2017) and many other stories in magazines and journals, I find that the pleasure of writing is precisely in that learning process.

How my stories develop…

I have no particular interest in the plot. All the stories have already been told. As the protagonist of Samuel Beckett’s Murphy says, ‘The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new’. What interests me is the voice, the style, the form of a narrative, or what one of Claire Keegan’s characters calls the ‘smell’.

To start with, I have no idea what the text might say. No message to share. Instead, a casual remark, an image, or an idea that emerges from reading others, that is from entering into a dialogue with a text, led me to start writing. Nor do I have a plan – that would be boring, rather like painting by numbers – I just let myself go. By that, I mean I try to live like a writer, that is, to keep my writing in mind regardless of what I am doing. I listen to my characters and as we gain each other’s confidence, they tell me more. And that is how the story emerges. Sometimes it is short, at other times, it has the length of a novel. I like to allow it to take shape, find its voice, its smell. That takes time and I know of no rules to tell me when that voice is right. I have to feel it. Of course, it is never completely right. Each text is bound to be a failure as it never matches the ideal one in my head. But failing means starting again, failing better, as Beckett teaches us.

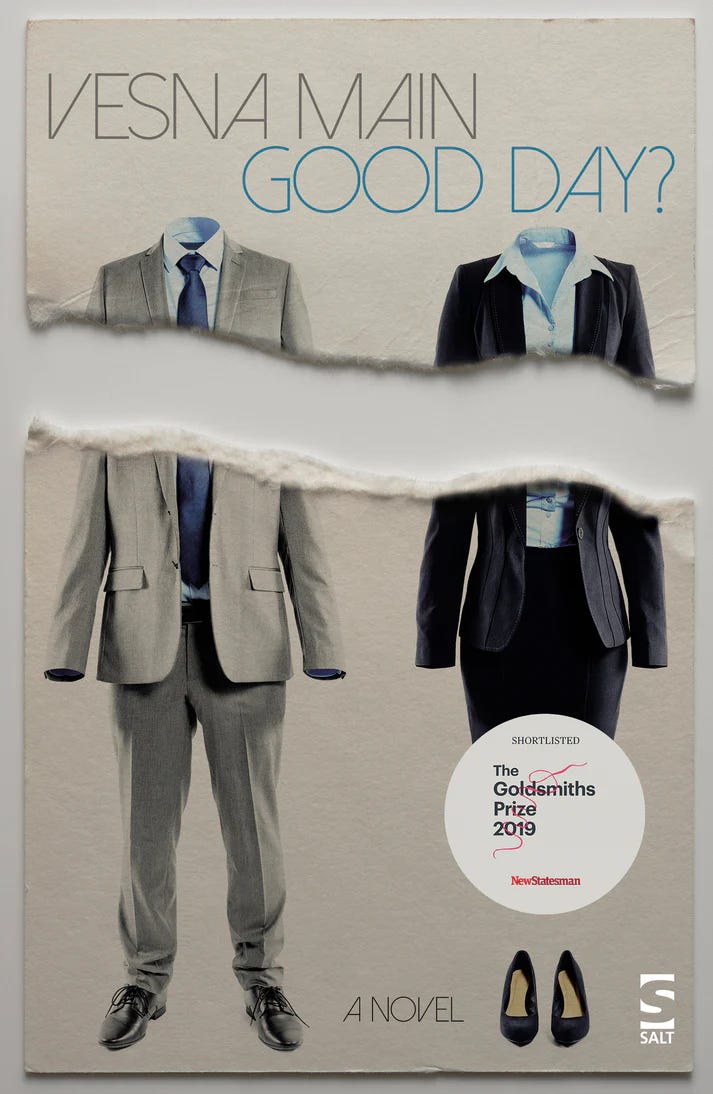

Good Day? (Salt, 2019) – shortlisted for the Goldsmiths prize – is a novel based around a marriage which crumbles when the wife discovers that the husband has been visiting prostitutes for many years. The original version was a traditional text, what literary theory calls ‘classic realist’, a form that I associate with the positivism of the 19th century and which I do not find appropriate for our uncertain times. I continued to seek another voice, a voice closer to Modernism, a voice that acknowledges the Nouveau Roman.

Then I hit upon the idea of a female novelist writing about a couple with a husband who visits prostitutes. Most sections start with the novelist’s husband asking her whether she has had a good day. She talks to him about her writing. He objects to her borrowing incidents from their life for her novel and criticises her presentation of the husband. Is she trying to trap him as she suspects that he too is visiting prostitutes? Gradually the lives of the fictional characters merge with those of the novelist and her husband. The novel is entirely written as a dialogue between her and him and that format worked for me. In other words, what I was and am always looking for is a form that suits the story, with its debate, and its characters. That is why each of my books takes on a different narrative form.

Only A Lodger … And Hardly That (Seagull Book, 2020), a novel about a search for identity, borrows the title from an 18th century freed slave, Ignatius Sancho, like me, an immigrant in letter and spirit. Starting with the premise that our identity, in part, comes from our ancestors, my alter ego seeks herself in her grandparents. Each section is written in a different style, reflecting each grandparent’s identity.

For example, as a child at family celebration tables, I was used to hearing that my paternal grandmother, when she was 16, had arranged to run away with a travelling circus but her bourgeois family stopped her. She was a dreamer, an artistic type who longed to be elsewhere and that idea, coupled with the family anecdote, led me to write her section as a sequence of short prose poems in which she meets a trapeze artist, and they fly hand in hand over the city, like Chagall’s lovers. The story of my paternal grandfather, a trade unionist and a party animal, is spun out of my readings of surviving family photographs. My maternal grandfather died before I was born and his section is a fantasy of what I imagined he might have been like.

How the idea for Waiting for a Party grew from a letter in a newspaper.

My latest novel, Waiting for A Party (Salt, 2024), was prompted by a letter in a national paper from a woman in her nineties who wrote that her partner of twenty years, a man in his eighties, had told her that he had found someone else. What upset her more than his abandonment was her inability to accept that she still had a desire for physical intimacy. I was moved and the woman stayed with me. Eventually, I heard her story. She told me much more than I could use in a novel. I wrote a version with chapters that chronologically followed her life even though I knew it would not work. But it allowed me to familiarise myself with her. I called her Claire Meadows.

And then one day, when I was swimming, I saw Claire, 92, lying in bed one Sunday morning and remembering another Sunday morning when she woke up after her first-ever orgasm with a man. By that time, she had been widowed after a 30-year marriage. That one-night stand made her aware of her sexuality and kick-started her personal development. She emerged from the confusion about who she was. And more than that. Throughout her marriage, she longed for a child but only became a mother once she was in her sixties. Magic? Technology? No. Better than that. All her own doing.

The image of her lying in bed, thinking of love, brought to mind Joyce’s Molly Bloom. In homage to her, Claire starts and ends her story with that eternal female ‘yes’.

Hers is a positive and necessary story. As she says, older women are not written about, they are written off. Since completing the novel, I have become aware that with, a few exceptions, there is hardly any fiction describing older women as sexual beings. Claire Meadows, however, still uses her vibrator.

The characters in my next novel, Supper with Lolita, have just started to speak to me although, as yet, I am confused by the cacophony.

Thank you, Vesna for introducing us to Claire Meadows. Reading your words here, I am reminded of

’s Book On All Fours which is enjoying phenomenal success.May we find freedom of sexual expression in our elder years!

Waiting for a Party can be bought from Salt Publishing, Waterstones, Blackwells, and Amazon.

If you have a book coming out and would like to be featured in The Book Room, do get in touch. You can message me here, or email me at suereedwrites@gmail.com

These posts are free to all to read. However, if you feel able to support me in my work and writing, I’d be very grateful. I’ve kept subscriptions to just £5 a month or less if you sign up for the year, making it just 96p a week.